/ The woman behind Vampira: Maila Nurmi photographed at the Seventh Primetime Emmy Awards on 7 March 1955 at the Moulin Rouge nightclub in Los Angeles. As her biographer Sandra Niemi recalls, "She wore an ice-blue evening gown, her hair dyed to match, and a rented fur stole draped around her shoulders." /

First, some caveats about this account of the life and times of wraith-cheekboned atomic-era horror movie hostess, pin-up model and actress Vampira (aka Maila Nurmi, 1922 - 2008). That title is unwieldy. The misjudged cover design is offputtingly amateurish. The prose would have benefited from the hand of a professional ghost writer. Author Sandra Niemi (Maila Nurmi’s niece-turned-biographer) frequently gets bogged-down in minutiae, especially (and perhaps understandably) when it comes to the Niemi family history. (A quick explanation: Maila Nurmi’s real name was Maila Elizabeth Niemi). All you really need to know about Nurmi’s origins is that she emerged from a poor family of Finnish immigrants, with a deeply conservative and disapproving father and an alcoholic mother.

But stick with Glamour Ghoul. It’s clearly a labour of love and ultimately a gripping account of an eccentric and tenacious survivor (some might say “failure”) who existed on the fringes of Hollywood for decades. Like the doomed Barbara Payton or her one-time director Ed Wood Jr, Nurmi endured obscurity and grinding abject poverty for most of her life. Yes, The Vampira Show on KABC-TV in Los Angeles rocketed her to fame and made her a pop culture sensation, but that success was ephemeral (her show was only on air between 1954 -1955) and Nurmi never made a cent even at her fleeting apex.

When The Vampira Show was

abruptly cancelled following a dispute with the broadcasters, Nurmi’s career

dramatically fizzled-out and never recovered. She also alienated many by seemingly

exploiting for publicity her friendship with James Dean following his death in

1955. By the time Nurmi appeared in Plan 9 from Outer Space she was widely considered

washed-up and a show business pariah. All her scenes were filmed in one day,

she was paid a grand total of $200 for her performance (the union minimum) and

she was presumably glad to get it.

Plus, the volatile Nurmi was nuts and self-sabotaging, burning bridges and making terrible career decisions at every turn. (Boy, did Nurmi need good management and financial advice). It also didn’t help that she lost her health and looks early. While still in her forties Nurmi was struck down with the debilitating autoimmune disease pernicious anemia. The side effects included losing many of her teeth and meant she walked with a cane for rest of her life. Niemi speculates her aunt’s illness was caused by malnutrition, partly from sheer poverty and partly from Nurmi starving herself to maintain the freakily emaciated 19" waist that was an essential component of the Vampira image. (By today's standards, we'd say Nurmi had an eating disorder).

/ Kim Novak and Vampira /

Nurmi was terminally unlucky in love, too - with one exception. God knows Marlon Brando was a messy, complicated and deeply flawed person but he was a rare savior in Nurmi’s life. To his credit, once their brief romance cooled, they remained long-term platonic friends and he just about kept Nurmi afloat in later years by paying her a modest allowance. (Brando did eventually cut her off, though). Otherwise Nurmi’s taste in men (with a preference for younger pretty boys) was disastrous. (Interestingly, she clashed with powerful gay agent and “the man who invented Rock Hudson” Henry Willson: they liked the same type). While Niemi herself never comes to this conclusion, it’s clear Nurmi either possessed defective “gaydar” or was primarily sexually attracted to unavailable gay men. For example, she was obsessed with the manipulative and sexually ambivalent young Antony Perkins and seethed with frustration that he didn't return her ardor.

If Brando was the hero, then Orson Welles was the villain of Nurmi’s life. She first encountered him aged 18 when she arrived in Hollywood in 1940 in pursuit of stardom. Welles took the naïve starlet’s virginity – and impregnated her. Unfortunately for Nurmi, he was engaged to Rita Hayworth at the time. After Welles callously abandoned her, the baby boy was quietly put up for adoption. Once Niemi uncovers this long-suppressed family secret, she commits herself to locating and contacting the long-lost son of Orson Welles and Vampira. (Did she succeed? I won’t spoil it. You’ll have to read the book).

On a lighter note, in 1956 Nurmi enjoyed a short-lived fling with 21-year-old Elvis Presley in Las Vegas. At the time, Nurmi was guest starring in Liberace’s spectacular revue at The Riviera and the embryonic Elvis was bombing nightly to hostile audiences at The New Frontier. Recognizing a kindred spirit, Nurmi was initially dazzled by the rockabilly hepcat’s rebel style (she admired his turquoise dinner jacket and noted, “Never before had I seen a straight man … and I assumed he was … wear eye shadow and eyeliner and was that mascara as well?”). But she was bluntly critical of his sexual expertise (“he made love like an adolescent”) and their relationship ended abruptly one night when in a fit of pique (Elvis was paying her insufficient attention), Nurmi - in her own words - “grabbed his pee-pee in a public place and he never forgave me.” But never mind that. Imagine the hallucinatory trio of Vampira, Liberace and Elvis hanging out together in Las Vegas in the fifties. The mind reels!

/ The February 1956 issue of gossip magazine Whisper via /

The other essential male presence in Nurmi’s life, of course, was her friend James Dean. They met when she was 31 (and finally finding belated success on television as Vampira after years on the margins) and he was still an unknown 23-year-old actor on the ascent. Just how intimate they were is contested (some Dean biographers argue Nurmi embellished their friendship). Niemi takes her aunt’s version as gospel (and doesn’t question Nurmi’s claims that Dean’s ghost repeatedly contacted her from beyond the grave). For what it’s worth, on the topic of Dean’s much-debated sexuality, Nurmi was succinct: “At the time I knew him, he was seeing women, but he was basically bisexual.”

In her later years, with considerable justification Nurmi sued Cassandra Peterson (aka Elvira, Mistress of the Dark) for copyright infringement. (Nurmi lost, even though she had an overwhelmingly persuasive case. If – like me – you revere both Vampira and Elvira, the chapter about how Nurmi got swindled makes for painful reading. Nurmi was frail and destitute at the time, while the savvy Peterson would go on to amass a fortune from Elvira merchandise. We’ll inevitably get Peterson’s side of the dispute when her impending memoirs come out in September 2021).

/ Maila Nurmi as a beatnik poetess (with a pet rat) in The Beat Generation (1959) /

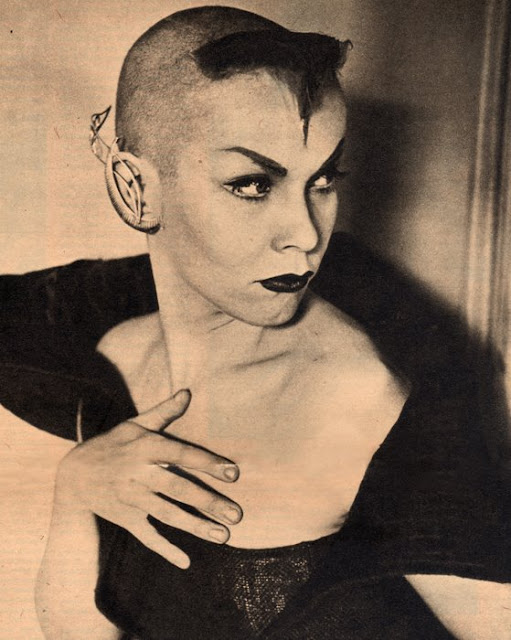

More happily, in the seventies and eighties Nurmi would be embraced by her spiritual offspring, punk musicians, particularly the bands inspired by lowbrow culture and horror b-movie imagery like The Misfits, The Screamers, The Damned, The Cramps and surf band Satan’s Cheerleaders (Nurmi recorded several tracks with the latter, which you can listen to on YouTube). Nurmi herself was obviously a punk ahead of her time. One thing Glamour Ghoul clarifies: there are some startling photos circulating online of a virtually bald Nurmi in the fifties sans the Vampira wig with brutally shorn hair, seemingly anticipating punk by about twenty years. Out of Vampira drag, Nurmi favoured a low-maintenance beatnik look of cropped-short blonde hair, Capri pants, sandals and shapeless sweaters. (You get a good impression of what the real Nurmi looked like in her cameo appearance as a beatnik poetess in 1959 film The Beat Generation). Niemi explains that when Nurmi’s stormy marriage to screenwriter Dean Riesner broke down, she chopped all her hair off in a bout of depression.

Weirdly, Niemi seems to skim over some intriguing aspects of Nurmi’s life and career. She doesn’t offer much insight into Nurmi’s participation in Ed Wood’s notorious 1959 sci-fi atrocity Plan 9 from Outer Space (to be fair, that’s been extensively documented elsewhere). We don’t glean much about how Nurmi came to be the live action model for the animated evil queen Maleficent in the 1959 Disney classic Sleeping Beauty. And I’d read elsewhere that Tim Burton exploited Nurmi badly when he made his 1994 biopic Ed Wood. If so, Niemi doesn’t mention it.

While Niemi strives to present her aunt in a sympathetic light, Nurmi doesn’t always emerge as terribly likable. Many of her career disappointments were self-inflicted. In the forties director Howard Hawks wanted to groom Nurmi for stardom as his next protegee (as he’d recently triumphantly done with Lauren Bacall). Nurmi scuppered that opportunity by flouncing off in a huff, complaining Hawks was taking too long. She also rarely had a good word to say about other women. Consider Nurmi’s scathing assessment of fiftysomething Mae West (one of Nurmi’s first acting breaks was appearing onstage in West’s 1944 play Catherine Was Great). “I saw that her movie star stature was only an illusion of the camera. She was really a tiny little biscuit of a girl. She wore an Aunt Jemima scarf tied round her weary peroxided hair and walked on tall awkward platform shoes. She wore a faded peignoir that likely began its life as pink but had since greyed with age. The garment was cut on the bias, revealing a surprisingly buoyant cleavage even as her pot belly gave away her age. She wore no makeup save for a huge pair of black nylon eyelashes. I didn’t understand why a purported legend could not afford a new bathrobe.”

Adopting the morbidly beautiful Vampira persona never made Nurmi rich or assured her stardom – but it gave her immortality. Still vivid, cartoon-ish, sexy and perverse, the irresistible image she created never grows stale, appealing to b-movie connoisseurs, punks, psychobillies, goths and the fetish subculture (with her extreme waist-cinching, Nurmi was a pioneer in body modification). And remember: at the time, she was perceived as a gimmick or one-woman publicity stunt. Decades later, Nurmi’s cadaverous cutie still haunts popular culture. The spell Vampira cast is seemingly eternal.

Further reading:

My analysis of Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959).