/ Tight skirt, tight sweater: the sensational Anna Magnani in Mamma Roma (1962) by Pier Paolo Pasolini /

Volcanic. Tempestuous. Explosive. Volatile. Ok, these are

all clichéd adjectives to use in the description of Italy’s greatest actress Anna Magnani – but hell, they’re accurate. The woman (revered as La Lupa by her

Italian fans) was a tigress, a seething torrent of raw emotion. Magnani was

dead by 1973 (Italy was plunged into mourning) and made relatively few films,

but she left behind a gallery of screen-scorching performances. I’ve loved her

in Rome: Open City (dir: Roberto Rossellini, 1945), L’Amore (dir: Rossellini,

1948), Bellissima (dir: Luchino Visconti, 1951) and The Golden Coach (Jean

Renoir, 1953).

/ My favourite portrait of La Magnani, taken in the early 1970s (so towards the end of her life). If you have to age, it may as well be like this! She was clearly a powerful and sensual presence right up until the end /

By the mid-50s, Magnani was so acclaimed in Europe that Hollywood

inevitably beckoned. Weirdly, her American films seem well and truly inaccessible

these days: I’ve never seen either The Rose Tattoo (1955) – for which she won

the Best Actress Oscar -- or Wild is the Wind (1957). They’re seemingly unavailable

on DVD in the UK and never crop up on TV.

For me Magnani steals Tennessee Williams adaptation The Fugitive Kind

(1959) from under the noses of co-stars Marlon Brando and Joanne Woodward, even

with the handicap of unfamiliar English (she apparently never properly learned

English and had to painstakingly learn her lines phonetically).

/ Magnani in Mamma Roma (1962). The surrounding urban decay (dotted with ancient ruins) feels desolate, almost lunar /

Magnani’s crowning achievement, though, is Mamma Roma

(1962), the film she made after returning to Italy after her stint in Hollywood.

(Accounts vary about whether Magnani was born in 1905 or 1908. Depending who you believe, she was her either

54 or 57 in Mamma Roma). The film is the highly politicised poet/provocateur Pier Paolo Pasolini's follow-up to his sensational debut Accattone (1961). (I’ve already

sang the praises of Accattone. I’ve seen Mamma Roma – one of my all-time

favourite films -- many times over the years; this time it was on the big

screen at The British Film Institute as part of their comprehensive two-month Pasolini

retrospective).

All of the essential components of Magnani’s persona are represented

in Mamma Roma: Earth mother. Feral she-wolf. Mother Courage. Mary Magdalene.

Noble whore. Fallen woman. Monstre

Sacrée. Gritty but kind-hearted ageing prostitute. Vital life

force. Every Italian woman who ever wore a black slip and shouted at someone

from her tenement balcony. Magnani portrays title character Mamma Roma

(sometimes referred to as “Signora Roma; we hear her actual surname -- Garofalo

– just once). The name implies she’s meant to personify the earthy, sensual, battered

but resilient essence or spirit of Rome itself.

/ Pasolini and Magnani during the filming of Mamma Roma /

(Pasolini reportedly later expressed ambivalence about

casting the internationally famous actress in the lead role: in the Italian

neo-realist tradition, he preferred using unknowns. His hesitation is impossible

to believe watching Mamma Roma today: Magnani’s fierce, vital and magnetic

performance anchors the film).

Magnani was a genuinely funny and ribald screen comedienne,

but I like her best suffering heavy emotional torment. Her entry into show

business in the 1930s was as a night club chanteuse – apparently she was like an

Italian Edith Piaf. Onscreen she pitches her performances the way the great

French chanson tragediennes Piaf and Juliette Greco sing their most tortured

songs. Certainly Magnani’s ravaged, careworn face, with its expressive dark

eyes and soulful under-eye bags, was ideal for evoking anguish.

Mamma Roma is a middle-aged prostitute who’s been walking

the streets for decades. (Italian neo-realist whores have great fashion sense;

Magnani mainly sports a tight pencil skirt and tight sweater-over-bullet bra

combo, with a patent leather handbag and killer stiletto heels). Along the way

she was forced to abandon her son Ettore (presumably he was raised by

relatives; Pasolini never clarifies). Finally liberated from the bondage of her

pimp and ex-lover Carmine, Mamma Roma is reunited with Ettore (now a teenager) and

strives to eke out a new, more respectable life for them together in dog-eat-dog

post-war / economic miracle-era Rome.

This theme of re-location from rural poverty to urban slum

(and the traditions and roots that get lost in the promise of modernity and progress)

particularly interested Pasolini. Like Accattone, Mamma Roma is set around the Roman

neighbourhoods Pigneto and Trastevere – then decrepit, now hip and gentrified.

I did some serious bar-hopping in Pigneto when I was in Rome in October 2010. To

channel the ghosts of Pasolini, Magnani, Luchino Visconti, Michelangelo Antonioni and Federico Fellini

I would have happily licked the cobbled pavement. (In reality I stuck to

drinking Campari and Prosecco).

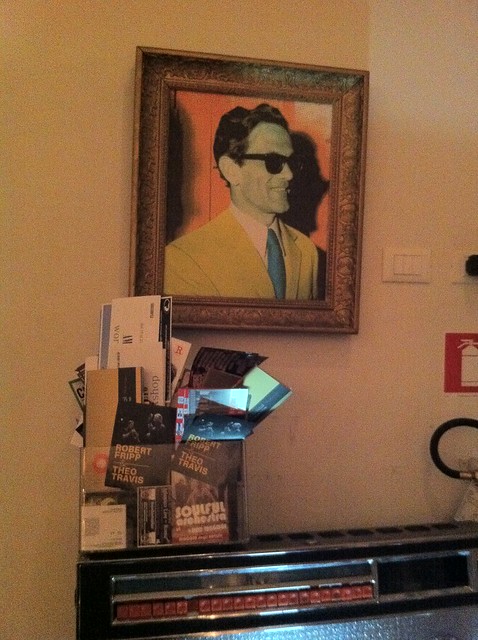

/ My photo of framed portrait of Pasolini above a vintage jukebox at Bar Necci in Pigneto, taken when I was there in 2010. It was in this neighbourhood Pasolini filmed his early masterpieces Accattone and Mamma Roma. See the rest of my Roman holiday pics on my flickr page /

Pasolini strove to transcend the conventions of Italian

neo-realism into his own idiosyncratic Cinema of Poetry. As with Accattone,

Pasolini tenderly ennobles the hardscrabble struggles of the impoverished

social underclass with a lyrical, painterly eye (framing characters like

they’re in a Renaissance painting) and employing classical music (in Accattone

Pasolini used Bach as an aural backdrop; in Mamma Roma, Vivaldi soars on the

soundtrack). This is a milieu of bare subsistence, in which hunger is a genuine

possibility. When people argue, someone inevitably pulls a knife; the

confrontation is probably observed by urchin children and a mangy third world stray

dog. The war-scarred landscapes are so decimated they look lunar. In the

background, a baby always seems to be crying. Mamma Roma and Ettore are cafoni,

the Italian equivalent of North American hillbillies. In the subtitles, there

are frequent disparaging references to “hicks”. Mamma Roma admonishes Ettore to

not speak like a hick (presumably in a rough, rural peasant dialect) but to talk

like she has learned to – like an

urban Roman.

Almost immediately, there are ominous premonitions things

won’t go well. The window to Ettore’s new bedroom offers a view of the local

cemetery. Worse, Mamma Roma is tracked down by Carmine, who blackmails her into

working the streets again. Carmine is

played by the swarthy, smouldering Franco Citti from Accattone (again playing a

pimp). This time around Citti sports a (deliberately?) unflattering sleazy

little moustache; it certainly makes him look like a seedy pimp. Magnani and

Citti’s confrontations crackle with violence – emotional, with the potential

for physical (you wouldn’t want to see Magnani lunging at you with a kitchen

knife and wild-eyed expression). I’m a total sucker for Franco Citti; he’s unforgettable

reminding Mamma Roma when he first met her, she was “covered in lice” and “didn’t

know what panties were.” “You knew it would end badly for one of us ...” he

snarls.

For swathes of Mamma Roma, Magnani vanishes and the action

centres on Ettore. As Magnani’s wayward

son, non-professional actor Ettore Garofolo (yes, the character is named after the actor who plays him) makes a haunting impression and

suggests a complex and troubled inner life. Pasolini’s camera tenderly explores his elfin

face (melancholic in repose), button nose and sorrowful dark puppy eyes, captivated. A

simultaneously tough and vulnerable man-child, he struts in the perfect sailor

roll (or in this context, pimp roll) even in the too-big suit his mother

insists he wear. As has already been pointed out, Garofolo can look like the pretty teenaged

street thug from a Caravaggio painting come to life. (Pasolini and Caravaggio

probably shared similar taste in rough trade).

Ettore is amoral, alienated. He rejects Mamma Roma’s

attempts to make him go to school or work, drifting instead towards petty crime

with the local juvenile delinquents. (Ettore’s gang are very much Pasolini’s

type and his camera caresses them in loving close-ups. In a nicely rakish

touch, one of Ettore’s cutest buddies is

missing a front tooth). It’s interesting to speculate Ettore has the makings

already of being the next Carmine. In her urgent mission to advance her

illiterate provincial son, Mamma Roma never stops to ask him what he actually

wants. When someone asks Mamma Roma,

"You’d hang on the cross for him, wouldn’t you?” she unhesitatingly replies, “What else is there?” Her maternal love is savage, primeval --

but Pasolini hints she’s also motivated by assuaging her own guilt for having

abandoned him and asks if maybe Ettore would have been more content to stay in the

countryside and be a labourer. Is what awaits him in Rome an “improvement”?

Pasolini’s most daringly audacious and avant-garde scenes depict

Magnani turning tricks at night on a grim stretch of road (recalling the

scrubby wasteland on the outskirts where Maddalena is beaten up in Accattone). These

are opportunities for Mamma Roma to relate her own history. It starts with her

fellow tarts (like loyal friend Biancofiore) and her “johns” asking Mamma Roma

to tell them her story, but as Magnani walks and speaks they gradually drift

away until it’s mainly Mamma Roma delivering heart-rending monologues about her

travails directly to the viewer, effectively breaking the fourth wall. She

speaks of brutal, grinding rural poverty and enforced marriage at age 14 to a relatively

wealthier, much older man.

/ Mamma Roma's friend and fellow prostitute Biancofiore (Luisa Loiano). With her beehive hairdo and heavy 1960s dark eye make-up, she looks like a J H Lynch painting come to life /

Pasolini keeps key details of Mamma Roma’s life vague and – confusingly – her accounts often contradict themselves. She married the corrupt older man, but also refers to having “married” Ettore’s criminal father – who was promptly hauled off to prison by waiting police men as soon as the ceremony ended. They’re clearly not the same man. How many husbands has Mamma Roma had? There’s a tantalising possibility that Carmine could be Ettore’s father. (Ettore himself expresses no curiosity about his father’s identity. A more conventional director would have explored this plot angle; Pasolini has different priorities). Mamma Roma’s stories meld the personal and the political: she rails against hypocrisy, Mussolini’s Fascism, injustice. In one soliloquy she describes the family of Ettore’s father as wretched scum, the lowest of the low (a police snitch, a beggar, a brothel madam) but points out “if they’d had money, they would have been good people” – perhaps the most powerful message of the whole film. In a moment of religious doubt, Mamma Roma looks skyward and angrily implores God, “Explain to me why I’m a nobody, and you’re the king of kings.”

As it progresses, Mamma Roma is increasingly characterised

by an overwhelming sense of dread. Outside maybe film noirs, it’s difficult to

find films more fatalistic than Mamma Roma or Accattone. It’s not a spoiler to reveal

that Mamma Roma (like Accattone) builds toward a tragedy that feels ancient,

epic, primal and operatic; Pasolini foreshadows this from almost the beginning.

It climaxes in a startling shot of a character filmed from above in a

crucifixion position so beautifully-composed, so suffused with Christ-like

suffering it makes you gasp.

Earlier there’s a wrenching moment when Mamma Roma abruptly

clamps her hand over her face and bursts into tears of sheer relief, believing that

things finally seem to be going in her favour -- all the degradation and

turmoil she’s suffered is seemingly justified. Of course she is wrong. The odds

(or the system) are stacked against her and Ettore before she even began. Mamma

Roma’s daring to improve her lot seems to enrage the gods. Fate punishes her.

It’s impossible to escape the past. Pasolini persuasively demonstrates that

mother and son are foredoomed by their environment and socioeconomic status. In

Accattone, Franco Citti seals his fate by defiantly declaring, “Either this

world kills me or I’ll kill it!” In Mamma Roma, Anna Magnani similarly swears, “I’ve

paid my dues in this life, and the next.” She lives to regret those words.

I always learn so much from your posts! I'm going to have to check her out. I'm ashamed to say that I'm not familiar with her but she sure sounded like an amazing lady.

ReplyDeleteGreat review i am now sure to watch.

ReplyDelete